Publicado en La Vanguardia del 22 de diciembre de 2006.... Los chimpancés del anuncio de la Marató de TV3 eran actores.... alguien se lo cree??

Approximately six per cent of human and chimp genes are unique to those species, report scientists from the University of Bristol and three other institutions.

The new estimate takes into account something that other measures of genetic difference do not – the genes that are no longer there. The research is reported in the inaugural issue of Public Library of Science ONE (Dec. 2006). The team studied "gene families" that are shared by humans, common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), mice, rats and dogs. Gene families are sets of genes in every organism's genome that are similar (or identical) because they share a common origin.

"After surveying gene families that are common to both humans and chimps, we observed in the human genome a significant increase in the duplication of various genes, including some that influence brain functions. This may provide new information about what it means to be human," says Nello Cristianini, Professor of Artificial Intelligence at Bristol University, who statistically analysed the data with specially created software tools.

The results support mounting evidence that the simple duplication and loss of genes has played a bigger role in our evolution than changes within single genes.

Cristianini and his research partners examined 110,000 genes in 9,990 gene families that are shared by humans, common chimpanzees, mice, rats and dogs. They found that 5,622, or 56 per cent, of the gene families they studied from these five species have grown or shrunk in the number of genes per gene family.

The researchers paid special attention to gene number changes between humans and chimps. Using a new statistical method developed by Tijl De Bie, University of Bristol, and Cristianini, the international team inferred humans have gained 689 genes (through the duplication of existing genes) and lost 86 genes since diverging from their most recent common ancestor with chimps. Including the 729 genes chimps appear to have lost since their divergence, the total gene differences between humans and chimps was estimated to be about 6 percent. The team included computational biologists from the University of Indiana and University of California, Berkeley.

The results do not negate the commonly reported 1.5 percent nucleotide-by-nucleotide difference between humans and chimps. But they do illustrate there isn't a single, standard estimate of variation that incorporates all the ways humans, chimps and other animals can be genetically different from each other.

Any measure of genetic difference between humans and chimps must therefore incorporate both variation at the nucleotide level among coding genes and large-scale differences in the structure of human and chimp genomes. Cristianini commented, "So the question biologists now face is not which measure is correct but rather which sets of differences have been more important in human evolution."

The finding complements reports by University of Colorado and University of Michigan researchers in the journals Science and PLoS Biology earlier this year, in which researchers showed that both gains and losses of individual genes have contributed to human divergence from chimpanzees and other primates.

Contact: Nello Cristianini

Això és el que contesta TV3 quan et queixes a títol individual per l'anunci de La Marató,

Sense comentaris,

Salut!

| Resposta del Servei d'Atenció 5430: |

| Aquest anunci no ha causat patiment a cap ésser viu, sinó que ha estat realitzat amb les màximes condicions de protecció per als animals que hi han intervingut. Tampoc se'ls sotmet a cap tractament degradant ni se'ls presenta de manera no coherent amb la seva condició (l'experimentació científica en psicologia i etologia amb ximpanzés és una pràctica legítima i acceptada). La simple visió de l'anunci mostra, al contrari, la gran tranquil·litat i bon grat en què els animals s'hi troben. Atentament, Televisió de Catalunya |

Benvolguts senyors,

Els vull fer arribar la meva disconformitat i rebuig per l’anunci que s’està emeten per la Marató d’enguany amb dos ximpanzés. En aquest anunci, i a qualsevol que empra ximpanzés, la crueltat potser no està en el moment del rodatge, però rotundament sí que ho està en el dia a dia de les seves vides i sobretot en el seu futur, que sol ser incert un cop passen dels 10 anys. Són animals socials molt intel·ligents, sensibles i longeus (poden sobrepassar els 60 anys) i viure tancats en petites gàbies, privats de tota relació social amb els seus congèneres, i sotmesos a uns ensinistraments que solen ser brutals, està ben lluny del que es pot entendre com una bona vida.

Anuncis com aquest, per molt bona intenció que tinguin, maleduquen al públic, i això fomenta la demanda d'espècies exòtiques, i sovint en perill d'extinció, com a animals de companyia. Això, evidentment, també impulsa el tràfic il·legal d'espècies. Segons la primatòloga i premi d’Astúries, Dra. Jane Goodall, per cada ximpanzé capturat pel tràfic il·legal d'espècies, en moren entre 10 i 30 individus. Crec que és una dada a tenir en compte, tractant-se d'un primat que ja està en greu perill d'extinció, abans de fomentar actuacions errònies amb anuncis com aquest.

S'ha de pensar més enllà del plató. I pensar que la televisió,a més d'entretenir, ha d'educar. Tots els esforços d’anys que s’estan duent a terme per conscienciar a la gent a ser més respectuosos amb el medi ambient i els animals es poden veure truncats amb un simple anunci de poc més d’un minut. Demano així que es deixi d'emetre aquest anunci i es canviï per un altre.

Nom:

Cognoms:

Apreciados señores/as,

Les quiero hacer llegar mi disconformidad y rechazo por el anuncio que se está emitiendo para la Marató de TV3 de 2006 en el que se utiliza a dos chimpancés. En este anuncio, y en cualquier otro que recurra a chimpancés, quizá la crueldad no esté en el momento del rodaje pero rotundamente sí que lo está en el día a día de sus vidas y sobre todo en su futuro, que suele ser incierto una vez pasan de los 10 años. Los chimpancés son animales sociales muy inteligentes, sensibles y longevos (pueden llegar a sobrepasar los 60 años) y vivir encerrados en pequeñas jaulas privados de toda relación social con sus congéneres y sometidos a entrenamientos que suelen ser brutales, está muy lejos de lo que se puede considerar una buena vida.

Anuncios como este, por muy buena intención que se tengan, maleducan al público y ello fomenta la demanda de especies exóticas, y a menudo en peligro de extinción, como animales de compañía. Ésto, evidentemente, también impulsa el tráfico ilegal de especies. Según la Dra. Jane Goodall, reputada primatóloga y premio Príncipe de Asturias, por cada chimpancé capturado para el tráfico ilegal de especies, mueren entre 10 y 30 individuos. Creo que se trata de un dato a tener en cuenta antes de fomentar actuaciones erróneas con anuncios como éste, considerando que los chimpancés son primates en un grave peligro de extinción.

Se tiene que pensar más allá del plató. Y pensar que la televisión, además de entretener tiene que educar. Todos los esfuerzos de años que se están llevando a cabo para concienciar a las personas a ser más respetuosos con el medio ambiente y el mundo animal puede verse truncado con un simple anuncio de poco más de un minuto. Les solicito de esta manera que se deje de emitir el anuncio y se cambie por otro.

Atentamente,

Nombre:

Apellidos:

La utilització de primats en publicitat i altres medis similars té un impacte negatiu sobre els esforços de conservació d’aquesta espècie que es troba en un greu perill d’extinció (Butynski y Members of the Primates Specialist Group, 2000), fomentant el tràfil il·legal d’aquestes espècies i contribuint a empitjorar lamentablement la situació en la que es troben els primats en els seus llocs d’origen (Feliu y Llorente, 2005).

Els primats són éssers socials per naturalesa. Avui dia, existeix el consens general que els primats necessiten de la companyia social d’altres individus de la seva espècie (Reinhardt y Reinhardt, 2000). Des del punt de vista del benestar animal, és molt important mantenir a aquests animals socials en unes condicions que els hi permeti desenvolupar un gran repertori de conductes pròpies de la seva espècie. D’aquesta manera, el benestar animal és directament proporcional a la integració que té en un grup (Feliu y Llorente, 2005). Fins ara, la resocialització és l’únic camí per tal de proporcionar a qualsevol ximpanzé captiu l’oportunitat de convertir-se en un individu normal i social (Fritz, 1986), però resulta molt complicada, llarga, costosa i moltes vegades impossible (Brent, Kessel, y Barrera, 1997). Un cop retirats del món de l’espectacle i la publicitat quan arriben a l’etapa adulta, aquests animals acostumen a trobar-se en un estat físic i condicions psicològiques molt pobres amb la conseqüent necessitat de rehabilitació i resocialització (Nash, Fritz, Alford, y Brent, 1999).

Els individus que han viscut en una situació de deprivació psicosocial mostren estar infraequipats física i psicològicament per a enfrontar-se o superar situacions estressants (Sackett, Novak, y Kroeker, 1999; Turner, Davenport, y Rogers, 1969; Vandenbergh, 1989) com la que implica l’enregistrament d’un anunci publicitari, o la seva participació en d’altre tipus d’espectacle. De la mateixa manera, alguns autors han proposat quatre possibles mecanismes a tenir en compte a causa dels efectes de les primeres experiències d’aquests animals durant la seva etapa infantil i adolescent (Sackett, 1970):

- Degeneració: la privació durant la infantesa pot produir una degeneració estructural i bioquímica irreversible en els sistemes cerebrals.

- Fracàs en el desenvolupament: no pot haver-hi un correcte desenvolupament fisiològic i estructural del cervell, o aquest pot no ésser complet, si no es produeix en un ambient ric en estimulació propi o similar al de l’espècie de l’individu.

- Dèficits d’aprenentatge: La privació durant la infantesa pot dificultar l’aprenentatge de les respostes perceptives i motores per tal de fer front durant l’etapa adulta a la solució de problemes que impliquin l’adaptació de l’individu al seu entorn.

- Trauma emocional: es pot produir un estrès emocional que afavoreixi conductes com la por, angoixa, desorientació, inatenció, evitació o conducta escapatòria.

Com hem vist, aquests entorns de deprivació social en primats poden tenir efectes de per vida sobre el desenvolupament psico-socio-emocional dels individus: conductes patològiques, excessiva humanització o incapacitat per a establir vincles amb els individus de la seva espècie (Lilly, 1994), i efectes sobre la bioquímica cerebral i la funció inmunitària davant d’estímuls estressors (Coe, 1993).

Els ximpanzés utilitzats per a la publicitat són separats de les seves mares quan són cries. Aquest fet és extremadament greu ja que en llibertat aquest individus romanen amb la seva família fins a l’edat de vuit anys (Goodall, 1986). D’aquesta manera, s’està produint un mal psicològic irreparable, ja que la separació traumàtica d’un primat superior del seu grup natural, o de la seva mare, provoca estrès e inseguretat que poden ocasionar dificultats en el seu desenvolupament posterior com a adult (Abelló, 1999), o simplement com a membre de la seva espècie. D’igual manera, els entrenaments als que estan sotmesos aquests animals requereixen de subjectes obedients, amb el que en moltes ocasions es poden produir situacions d’abús físic i psicològic, ja que els mètodes d’entrenament acostumen a estar basats en la por i la domimanció.

A l’igual que els nens i nenes humans, els ximpanzés aprenen a través de l’observació dels adults e imiten el seu comportament. Ells aprenen en un context social i els individus que no tenen oportunitat de créixer en un grup normal no podran aprendre els comportaments propis de la seva espècie, amb el que probablement acabaran mostrant tota una gamma de conductes anormals. Aquest fet, podria dificultar enormement la seva capacitat de reintroducció a grups socials establerts, que al cap i a la fi és l’única alternativa de recuperació d’aquests individus.

Abelló, M. T. (1999). Coco. Revista del Parc Zoològic de Barcelona, 1, 33-35.

Brent, L., Kessel, A. L., y Barrera, H. (1997). Evaluation of introduction procedures in captive chimpanzees. Zoo Biology, 16, 335-342.

Butynski, T., y Members of the Primates Specialist Group. (2000). Pan troglodytes. En 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (www.iucnredlist.org). Recuperado el 18 de Julio de 2006.

Coe, J. C. (1993). Psychosocial factors and inmunity in nonhuman primates: A review. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 289-308.

Feliu, O., y Llorente, M. (2005). Chimpanzees and other state-owned primates in Spain: past, present and future. Folia Primatologica, 76(1), 51-52.

Fritz, J. (1986). Resocializacion of asocial chimpanzees. En K. Benirschke (Ed.), The Road to Self-Sustaining Populations (pp. 351–359). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Goodall, J. (1986). The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns fo behavior. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Lilly, A. A. (1994). External Stressor in Captivity. En V. Landau (Ed.), ChimpanZoo: 1994 Conference (Proceedings): The Jane Goodall Institute.

Nash, L. T., Fritz, J., Alford, P. A., y Brent, L. (1999). Variables influencing the origins of diverse abnormal behaviors in a large sample of captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). American Journal of Primatology, 48, 15–29.

Reinhardt, V., y Reinhardt, A. (2000). Social enhancement for adult nonhuman primates in research laboratories: a review. Lab Animal, 29(1), 34-41.

Sackett, G. P. (1970). Isolation mechanisms, rearing condicions and theory of early experience effects in primates. En M. R. Jones (Ed.), Miami symposium on prediction of behavior: Early experience. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press.

Sackett, G. P., Novak, M. F. S. X., y Kroeker, R. (1999). Early experience effects on adaptative behavior: theory revisited. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. Research Reviews, 5, 30-40.

Turner, C. H., Davenport, R. K., y Rogers, C. M. (1969). The effect of early deprivation on the social behavior of adolescent chimpanzees. American Journal of Psychiatry, 125, 1531-1536.

Vandenbergh, J. G. (1989). Issues related to "psychological well-being" in nonhuman primates. American Journal of Primatology, Supplement 1, 9-15.

Article URL: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=57516

Hiring Organization:

University of St Andrews

Date Posted:

2006-11-23

Position Description:

Applications are invited for an EU-funded postgraduate studentship (fees plus stipend) to study social learning processes in capuchin monkeys. The successful applicant will work under the supervision of Professor Kevin Laland and Dr Rachel Kendal to conduct experimental investigations evaluating social learning strategies in zoo-based populations of monkeys. The project is part of an EU NEST-Pathfinder initiative on cultural dynamics, and involves collaboration with a network of European researchers.

Qualifications/Experience:

The ideal candidate would have a degree in behavioural biology, and knowledge of social learning and cultural evolution.

Salary/funding:

Tuition fees plus stipend are provided.

Term of Appointment:

3 years, commencing 1 January 2007 or as soon as possible thereafter.

Application Deadline:

December 13th

Comments:

Applicants should submit a cover letter and CV detailing their qualifications and interest in the topic to Rachel Kendal from whom further information may be obtained.

Contact Information:

Dr Rachel Kendal

School of Psychology, University of St Andrews

St Andrews, Fife KY16 9JP

United Kingdom

E-mail Address:

RachelKendal2003@yahoo.co.uk

Hiring Organization:

Leipzig School of Human Origins

Date Posted:

2006-11-23

Position Description:

We invite applications for the Leipzig School of Human Origins, a joint graduate program of the University of Leipzig (Germany) and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

This program provides interdisciplinary training and research opportunities for university graduates who wish to work towards a PhD in anthropology, biology, evolutionary genetics, primatology, paleoanthropology and related fields. Each student will apply for - and be accepted to - one of the following disciplines:

1) Comparative primatology -- focusing on the evolution of social and cultural systems in the great apes, as well as other relevant mammals.

2) Evolutionary and Functional Genomics / Ancient DNA / Molecular Anthropology

a. Evolutionary genomics / Ancient DNA -- focusing on the evolutionary and functional genomics of humans and the great apes, as well as the retrieval of DNA from palaeontological remains.

b. Molecular Anthropology - focusing on the origin, relationships, history, and migration patterns of human populations.

3) Human Paleontology, Prehistoric Archaeology and Archaeological Science -- focusing on the study of hominid fossils and archaeological sites. This includes comparative morphological as well as chemical (isotopic) analyses.

Graduate students will be accepted to one of these areas but will have the opportunity to take part in courses and seminars in all of them. Our PhD program is open for international students and is designed as a 3-year-program.

Qualifications/Experience:

We invite applications from all countries. Applicants must hold a Masters degree, a Diploma or equivalent in biology, biochemistry, anthropology, or related fields.

It is not necessary to hold the degree at the point of application. However, you must have been awarded your degree prior to the start of the program in September.

Candidates have to be fluent in written and spoken English. German is not required but international students will be offered opportunities to take German courses.

Salary/funding:

PhD students are supported by pre-doctoral fellowships which are provided either by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology or the University of Leipzig; or have been obtained by the student.

Term of Appointment:

Fall 2007

Application Deadline:

January 31, 2007

Comments:

Leipzig is a highly livable city in the center of Europe (www.leipzig.de).

Contact Information:

Sandra Jacob

Deutscher Platz 6

Leipzig, Saxony 04103

Germany

Telephone Number:

++493413550122

Fax Number:

++493413550119

Website:

http://www.leipzig-school.eva.mpg.de

E-mail Address:

leipzig-school@eva.mpg.de

Hiring Organization:

Inés Nole

Date Posted:

2006-11-23

Position Description:

I am looking for volunteers to assist with the data collection for my investigation “Intestinal parasite loads of a Neotropical Primate measured in disturbed and undisturbed forests”.

The aim of this project is to understand the human influence on parasite infection in a wild species of a Neotropical Monkey.

Fieldwork will take place at the Los Amigos Research Center (CICRA) – Madre de Dios – Perú, Check out the website: http://www.amazonconservation.org/home/LosAmigos/cicra.htm for more information about the station. Fieldwork will take place around the station and will involve mainly behavioural observations of titi monkeys (Callicebus brunneus) and collection of fecal samples for the diagnosis of intestinal parasites. Volunteers should be prepared to work long hours and under hot weather.

Qualifications/Experience:

I am looking for enthusiastic, hard-working and reliable individuals who possess a strong interest in primates to assist me for a period of one to four months between February and May 2007.

Salary/funding:

Accommodation, transportation and food expenses to the field site must be provided by the volunteer. Volunteers will also have to fund their own travel to Perú.

Support provided for internship/volunteer positions (travel, meals, lodging):

Estimated costs are as follows:

TRANSPORTATION

Roundtrip airfare US to Lima, Peru: $1,000-$2,000

Roundtrip airfare Lima to Puerto Maldonado, Peru: $200

Roundtrip bus fare Puerto Maldonado to Laberinto, Peru: $20

Roundtrip boat fare Laberinto to the Field Station (CICRA): $50-$245

Station Fees at CICRA:

- Room, board, and food: $20/person/day

Application Deadline:

December 10th 2006

Comments:

APPLICATIONS

Applications should include:

- Current CV or resume

- A brief description of yourself including your interest in primates and any relevant experience (i.e. field/laboratory experience, outdoor experience, etc.)

APPLICANTS SHOULD:

- Be enthusiastic and genuinely interested in primates.

Contact Information:

Inés Nole Bazán

Jr. Cornelio Borda 278 dep 202

Lima, NA 01

Peru

Telephone Number:

4251447

E-mail Address:

inesnole@hotmail.com

Males prefer older females, at least in the chimp world, scientists now report.

These findings, reported in the Nov. 21 issue of the journal Current Biology, could shed light on how the more chimp-like ancestors of humans might have behaved, said researcher Martin Muller, a biological anthropologist at Boston University.

Human men often prefer young women. One reason for this, scientists propose, lies in the human proclivity to form unusually long-term mating pairs. When combined with the natural urge to beget as many children as possible, since a woman's fertility is limited by age, men would find young women more sexually attractive.

Chimpanzees, unlike humans, do not form mating partnerships for long, and are instead promiscuous. Moreover, female chimps show no evidence of menopause, which means their fertility is not limited by age. This suggested male chimps might not care about the age of a mate as humans do.

Older is better

To test this prediction, Muller and his colleagues at Harvard investigated chimpanzees [image] at Kibale National Park in Uganda for eight years.

"It takes a lot of effort to find them in the forest and to follow them through a lot of thick vegetation and to try and record all this," Muller recalled.

Surprisingly, the scientists found male chimps preferred older females. Males approached older females more often for sex, and preferred clustering around older females that were in heat. Older females also had sex more frequently with high-ranking males and more regularly triggered male-on-male aggression during mating contests.

"The stereotypical view of human mating involves males wanting to be promiscuous and females being coy, but in chimps you see young females being very interested in mating with all the males, maybe going male to male and presenting their sexual swellings, sometimes grabbing their penis and playing with them, and the males just ignore them," Muller told LiveScience.

By Charles Q. Choi

Special to LiveScience

posted: 20 November 2006

12:01 pm ET

Reasons unclear

It remains uncertain as to why male chimps would prefer older females, as opposed to not caring about age at all.

"Hormonal data collected noninvasively from urine samples suggest older females are more fecund. Perhaps this is a matter of their higher rank— older females tend to be dominant over younger ones, which gives them preferred access to the best foods, so they may be more likely to conceive," Muller said.

In addition, the older females get, the more fit they might show themselves to be against the hardships of life, and thus could lead to equally robust children, which males could find attractive. Alternatively, older females might have accumulated mothering experience, leading to increased infant survivorship. "Or it might be any combination of these, or all of them," Muller said.

To tease out why exactly human men favor young women and chimp males prefer older females, Muller suggested researching what other primate males look for, such as gibbons, who like humans form long-term mating pairs but like chimps do not have menopause.

Fuente: LiveScience

Hiring Organization:

State University of New York, Oneonta and DANTA: Association for Conservation of the Tropics

Date Posted:

2006-11-15

Position Description:

The State University of New York at Oneonta and Danta: Association for Conservation of the Tropics are pleased to announce a Primate Behavior and Conservation Field Course to be held in Costa Rica from June 12, to July 11, 2007. This program is open to people of all academic backgrounds. Participants may enroll on either a credit or non-credit basis. Also, an optional ecotravel experience will be provided for those who wish to stay longer for travel after the course.

The course will be held at El Zota Biological Field Station in North-eastern Costa Rica. The course is designed to provide students with training in primate behavior, ecology and conservation in a field setting. During the first half of the course, students will learn how to (1) collect data on the behavior of free-ranging primates, (2) measure environmental variables, including assessment of resource availability, (3) measure population size, and (4) map the field site. In the second half of the course, in consultation with the instructor, each student carries out an independent research project. Students in the past have investigated such topics as feeding ecology, positional behavior, and habitat use in the mantled howler monkey, white-faced capuchin and black-handed spider monkey. Students will be involved in applied conservation during a 6 day field trip to Puerto Viejo and Punta Mona.

The cost of the course is $1850, and includes all within-country transportation, room and board, and expenses for a 6 day field trip. It does NOT include your international flight, airport taxes ($25), accommodation and meals for the first and last nights in San Jose. The deadline for registration is May 1, 2007. Enrollment is limited to 25 participants.

To learn more about the Primate Behavior and Conservation field course, please visit our website (www.danta.info), or email us at dingeska@oneonta.edu.

Qualifications/Experience:

The course is intended for undergraduates or early graduate level students who are very interested in tropical biology, but have little or no experience of working in a tropical environment.

Application Deadline:

May 1, 2007

Contact Information:

Kimberly Dingess

31 Pine Street

Oneonta, NY 13820

USA

Telephone Number:

607-432-0315

Website:

http://www.danta.info

E-mail Address:

dingeska@oneonta.edu

Exposició "Atapuerca i l'evolució humana"

Exposició "Atapuerca i l'evolució humana" Tallers:

Els taller es faran els dies 25, 26 de novembre, el 2, 3, 16 i 17 de desembre i el 13 i 14 de gener. Monitors de suport.

Dia 25, taller d’arqueologia de 12 a 13,30 i el de paleontologia, de 18 a 19,30.

Dia 26, taller d’art prehistòric de 12 a 13,30.

Dia 2 i 3, els mateixos horaris del cap de setmana 25 i 26.

Dia 16 i 17, els mateixos horaris del cap de setmana 25 i 26.

Dia 13 i 14, els mateixos horaris del cap de setmana 25 i 26.

Visites guiades:

OBERTES: Les visites es faran cada dia a les 7 de la tarda.

Els dissabtes i festius se’n farà dues : una al matí a les 12 i una al vespre a les 7. (possibilitat d’ampliar a 2 a les tardes).

ESCOLARS: a petició (presumiblement en horari de 10 a 12 o de 15 a 16).

La mostra està organitzada per la Fundació Caixa de Catalunya i Casa de Cultura. Per a més informació: 972.20.20.13

By Ann Gibbons

ScienceNOW Daily News

9 November 2006

With their huge molars and massive jaw muscles, australopithecines have been portrayed as nutcrackers who crunched their way through seeds, nuts, and pulpy fruits. As Africa grew cooler and drier, however, these critical fall-back foods were hard to come by, supposedly leading to the hominid's downfall.

To test this theory, a team of American and British researchers studied the teeth of four individuals of Paranthropus robustus (also known as Australopithecus robustus) from the Swartkrans Cave in South Africa. The team scanned the teeth with a sensitive laser, which did not destroy the teeth but etched them lightly enough to free carbon gases long trapped in the enamel. Because different plants absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide differently, the researchers were able to see what types of vegetation the hominids ate based on the ratio of carbon isotopes in their teeth.

Their cuisine included a mix of tropical grasses and sedges, along with woody fruits, shrubs, and herbs, according to the findings. What's more, carbon samples from ridges laid down like tree rings in a single tooth revealed that the hominids switched between these diverse plants, depending on the time of year. The pattern held, regardless of when the hominids lived. Although the specimens date back to about 1.8 million years ago, each individual's lifetime was probably separated by thousands or tens of thousands of years, indicating that Paranthropus robustus was quite capable of dealing with changes in climate or different habitats. "We didn't expect to see as much variability as we found," says lead author Matt Sponheimer of University of Colorado at Boulder. "It was quite a surprise."

The new method is a huge improvement over old isotopic studies that required anthropologists to drill--and destroy--teeth to sample carbon, like prehistoric dentists, says paleoanthropologist Fred Grine of the Stony Brook University in New York. "Sponheimer's taken the analysis of carbon isotopes in fossils to a new level of sophistication," he says, adding that he hopes that fossil teeth--and diets--of earlier hominids can also be studied with the new nondestructive method.

Fuente: Science: http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2006/1109/1?etoc

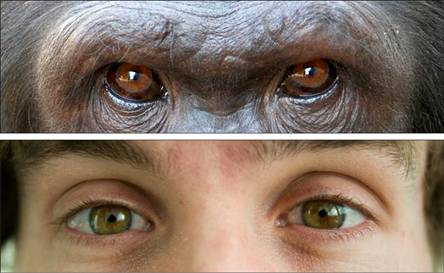

Researchers test ‘cooperative eye’ hypothesis in humans and apes

By Ker Than

LiveScience

Updated: 7:57 p.m. ET Nov. 8, 2006

For humans, the eyes are more than just windows to the outside world. They are also portals inward, providing others with glimpses into our inner thoughts and feelings.

Of all primates, human eyes are the most conspicuous; our eyes see, but they are also meant to be seen. Our colored irises float against backdrops of white and encircle black pupils. This color contrast is not found in the eyes of most apes.

According to one idea, called the cooperative eye hypothesis, the distinctive features that help highlight our eyes evolved partly to help us follow each others' gazes when communicating or when cooperating with one another on tasks requiring close contact.

In a new study that is one of the first direct tests of this theory, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany looked at what effect head and eye movements had on redirecting the gaze of great apes versus human infants.

In the study, a human experimenter did one of the following:

Results showed that the great apes — which included 11 chimpanzees, four gorillas and four bonobos — were more likely to follow the experimenter's gaze when he moved only his head. In contrast, the 40 human infants looked up more often when the experimenter moved only his eyes.

The findings suggest that great apes are influenced more by head than eyes when trying to follow another's gaze, while humans are more reliant on eyes under the same circumstances.

The study, led by Michael Tomasello, will be detailed in an upcoming issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.

The small things

Kevin Haley, an anthropologist at the University of California at Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study, told LiveScience he thinks the cooperative eye hypothesis is quite plausible, especially "in light of research demonstrating that human infants and children both infer cooperative intentions in others and display cooperative intensions themselves."

Comparisons of human eyes to those of other primates reveal several subtle differences that help make ours stand out. For example, the human eye lacks certain pigments found in primate eyes, so the outer fibrous covering, or "sclera," of our eyeball is white. In contrast, most primates have uniformly brown or dark-hued sclera, making it more difficult to determine the direction they're looking from their eyes alone.

Another subtle aid that helps us determine where another person is looking is the contrast in color between our facial skin, sclera and irises. Most apes have low contrast between their eyes and facial skin.

Humans are also the only primates for whom the outline of the eye and the position of the iris are clearly visible. In addition, our eyes are more horizontally elongated and disproportionately large for our body size compared to most apes. Gorillas, for example, have massive bodies but relatively small eyes.

The cooperative eye hypothesis explains these differences as traits that evolved to help facilitate communication and cooperation between members of a social group. As one important example, human mothers and infants are heavily reliant on eye contact during their interactions. One study found that human infants look at the face and eyes of their caregiver twice as long on average compared with other apes.

Clue to our humanity

Other ideas have also been proposed to explain why humans have such visible eyes. For example, white sclera might signal good health and therefore help signal to others our potential as a mate.

Or, as one other recent study suggested, visible eyes might be important for promoting cooperative and altruistic behavior in individuals that benefit the group. The study, conducted by Haley and Daniel Fessler, also at UCLA, found that people were more generous and donated more money if they felt they were being watched — even if the watchful eyes were just drawings resembling eyes on a computer screen.

Tomasello and his team note in their paper that "these hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, and highly visible eyes may serve all of these functions."

If correct, the cooperative eye hypothesis could provide a valuable clue about when we became the social beings that we are. “It would be especially useful to know when in evolution human's highly visible eyes originated, as this would suggest a possible date for the origins of uniquely human forms of cooperation and communication,” Tomasello and colleagues write.

© 2006 LiveScience.com. All rights reserved. 13:35 08 November 2006

NewScientist.com news service

Roxanne Khamsi

They may be cold-blooded, but some lizards have warm personalities and like to socialise, a new study shows.

A behavioural study reveals that lizards have different social skills: some are naturally inclined to join large groups while others eschew company altogether. The discovery of reptilian personality types could help ecologists better understand and model animal population dynamics, say the researchers involved.

Scientists define "personality differences" as consistent behavioural differences between individuals across time and contexts. But there is a need for more research on these differences in wild animals, says Julien Cote of the Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris, France. "Psychologists have explored the considerable range of non-human personalities like sociability, but mostly on domesticated animals," he says.

Cote and colleagues captured wild pregnant common lizards (Lacerta vivipara), and as soon as the offspring were born they were exposed to the scent of other lizards, to test their reactions. Over the next year the team monitored the newly born creatures to see how much time each spent in different areas of their enclosure.

Lizards that showed an aversion to other scents at an early age were more likely to flee highly populated areas of the enclosure, Cote's team found. These lizards were described as "asocial". In contrast, those that had been initially attracted to other scents often left sparsely populated areas of the enclosure to seek out areas of higher population density.

Understanding these personality differences in wild animals could give ecologists a more nuanced view of population dynamics, Cote says. "When studying and modelling how populations function, it is necessary to consider different kinds of individuals reacting differently to the environment rather than a unique behavioural response for all individuals."

Other experts agree that personality types could help explain why some animals might be more reluctant to leave a group and explore new turf. "If you have a personality by definition you are constrained," says ecologist Jason Jones of Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, US.

Journal reference: Proceedings of the Royal Society B (DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3734)

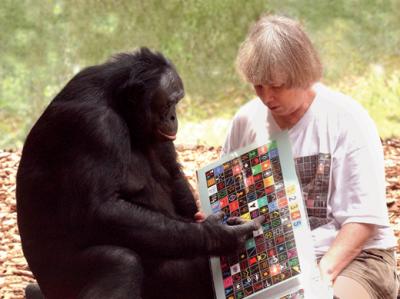

Follow the leader?

Chimps in captivity follow the leader and place orange plastic token in a container to receive a reward.

Credit: Yerkes National Primate Research Center

By Gretchen Vogel

ScienceNOW Daily News

3 November 2006

The behaviour in question involved objects that chimps would normally deem useless. Graduate student Kristin Bonnie of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues provided two groups of chimpanzees with either a bucket with a hole cut in the side or a container with a large tube sticking out of the top. Out of sight of the other group members, the researchers trained one high-ranking female from each group to deposit tokens into either the bucket or the tube. The team then sat back and watched to see if that trained behavior would spread.

Indeed, the other animals quickly realized that the trained group member was receiving treats--apple or banana slices--for picking up the tokens and placing them in a container. Although treats were available for chimps that used either receptacle, each group followed their leader and used just one of the two options. There was only one exception: A low-ranking female in one group figured out she could get rewards for using the second container, but none of her group members followed her lead.

Bonnie and her colleagues say the results, reported online this week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, suggest that the evolutionary roots of humans’ tendency to follow convention are also present in our chimpanzee cousins. While other studies have shown that different chimp groups use similar tools in different ways (ScienceNOW, 22 August 2005), this is the first controlled study that shows chimps can follow conventions that don’t involve tools, Bonnie says.

The experiment is "getting closer to the heart of cultural phenomena where you’re only doing something because it’s the local way of doing it," says study co-author Andrew Whiten of the University of St. Andrews in Fife, United Kingdom. But psychologist Michael Tomasello of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, says the experiment doesn’t cleanly demonstrate that chimps can pick up a completely arbitrary custom. Learning that performing a certain action results in a reward is not the same as doing something just because everyone else is doing it, he says.

Fuente: http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2006/1103/4?etoc

By Paul Raffaele

Robert Waterston El lunes, en CosmoCaixa-Barcelona. Foto: JOSEP GARCÍA" border="0" height="164" width="200"> Robert Waterston El lunes, en CosmoCaixa-Barcelona. Foto: JOSEP GARCÍA

Robert Waterston El lunes, en CosmoCaixa-Barcelona. Foto: JOSEP GARCÍA" border="0" height="164" width="200"> Robert Waterston El lunes, en CosmoCaixa-Barcelona. Foto: JOSEP GARCÍA

Los elefantes pueden reconocerse a sí mismos en un espejo como ya se había descubierto en el caso de simios y delfines, animales que como el ser humano poseen este sentido de conciencia, según un estudio de la Universidad Emory en Atlanta (Estados Unidos) que se publica en la edición digital de la revista de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias.

Los investigadores explican que este tipo de conciencia puede medirse a través del autorreconocimiento en el espejo. Un animal capaz de reconocerse ante el espejo suele progresar hacia otra serie de reconocimientos y observaciones, culminando en una prueba mediante la que es capaz de tocar una marca sobre su cuerpo que de otra forma no podría ver.

Esta capacidad de reconocerse en el espejo sólo se ha documentado hasta ahora en simios y delfines.

La prueba definitiva

Los científicos han realizado una prueba de reconocimiento ante el espejo en tres elefantes hembra asiáticos. Los tres elefantes han pasado varios niveles de pruebas frente al espejo. Por último, uno de los tres comenzó a tocar repetidamente una X que tenía sobre su cabeza con su trompa.

Aunque sólo uno de los elefantes ha pasado la prueba de tocarse la marca, los investigadores indican que menos de la mitad de los chimpancés evaluados habitualmente pasaban también esta prueba. En combinación con el hecho de que la progresión global fue paralela a la de simios y delfines, los elefantes pondrían por ello desplegar autoconciencia.

By ANDREW BRIDGES

The Associated Press

Monday, October 30, 2006; 11:02 PM

WASHINGTON -- If you're Happy and you know it, pat your head. That, in a peanut shell, is how a 34-year-old female Asian elephant in the Bronx Zoo showed researchers that pachyderms can recognize themselves in a mirror _ complex behavior observed in only a few other species.

The test results suggest elephants _ or at least Happy _ are self-aware. The ability to distinguish oneself from others had been shown only in humans, chimpanzees and, to a limited extent, dolphins.

That self-recognition may underlie the social complexity seen in elephants, and could be linked to the empathy and altruism that the big-brained animals have been known to display, said researcher Diana Reiss, of the Wildlife Conservation Society, which manages the Bronx Zoo.

In a 2005 experiment, Happy faced her reflection in an 8-by-8-foot mirror and repeatedly used her trunk to touch an "X" painted above her eye. The elephant could not have seen the mark except in her reflection. Furthermore, Happy ignored a similar mark, made on the opposite side of her head in paint of an identical smell and texture, that was invisible unless seen under black light.

"It seems to verify for us she definitely recognized herself in the mirror," said Joshua Plotnik, one of the researchers behind the study. Details appear this week on the Web site of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Still, two other zoo elephants, Maxine and Patty, failed to touch either the visible or invisible "X" marks on their heads in two runs of the experiment. But all three adult female elephants at the zoo behaved while in front of the jumbo mirror in ways that suggested they recognized themselves, said Plotnik, a graduate student at Emory University in Atlanta.

Maxine, for instance, used the tip of her trunk to probe the inside of her mouth while facing the mirror. She also used her trunk to slowly pull one ear toward the mirror, as if she were using the reflection to investigate herself. The researchers reported not seeing that type of behavior at any other time.

"Doing things in front of the mirror: that spoke volumes to me that they were definitely recognizing themselves," said Janine Brown, a research physiologist and elephant expert at the Smithsonian National Zoological Park in Washington. She was not connected with the study but expressed interest in conducting follow-up research.

Gordon Gallup, the psychologist who devised the mark test in 1970 for use on chimps, called the results "very strong and very compelling." But he said additional studies on both elephants and dolphins were needed.

"They really need to be replicated in order to be able to say with any assurance that dolphins and elephants indeed as species are capable of recognizing themselves. Replication is the cornerstone of science," said Gallup, a professor at the State University of New York at Albany, who provided advice to the researchers.

The three Bronx Zoo elephants did not display any social behavior in front of the mirror, suggesting that each recognized the reflected image as itself and not another elephant. Many other animals mistake their mirror reflections for other creatures.

That divergent species such as elephants and dolphins should share the ability to recognize themselves as distinct from others suggests the characteristic evolved independently, according to the study.

Elephants and mammoths, now extinct, split from the last common ancestor they shared with mastodons, also extinct, about 24 million years ago. In a separate study also appearing this week on the scientific journal's Web site, researchers report finding fossil evidence of an older species that links modern elephants to even older ancestors.

The likely "missing link" is a 27 million-year-old jaw fossil, found in Eritrea.

___

On the Net:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: http://www.pnas.org/

Fuente: The Washington Post

In a study of orangutans living on the Indonesian islands of Borneo and Sumatra, scientists from Duke University and the University of Zurich have found what they say is the first demonstration in primates of an evolutionary connection between available food supplies and brain size.

Based on their comparative study, the scientists say orangutans confined to part of Borneo where food supplies are frequently depleted may have evolved through the process of natural selection comparatively smaller brains than orangs inhabiting the more bounteous Sumatra.

The findings "suggest that temporary, unavoidable food scarcity may select for a decrease in brain size, perhaps accompanied by only small or subtle decreases in body size," said Andrea Taylor and Carel van Schaik in a report now online in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Taylor is an assistant professor at Duke's departments of Biological Anthropology and Anatomy and of Community and Family Medicine. Van Schaik directs the University of Zurich's Anthropological Institute & Museum, and he also is an adjunct professor of biological anthropology and anatomy at Duke, where he had worked for 15 years.

"To our knowledge, this is the first such study to demonstrate a relationship between relative brain size and resource quality at this microevolutionary level in primates," they said.

Such a change would provide support for what Taylor called the "expensive tissue" hypothesis. "Compared to other tissues, brain tissue is metabolically expensive to grow and maintain," she said. "If there has to be a trade-off, brain tissue may have to give."

"The study suggests that animals facing periods of uncontrollable food scarcity may deal with that by reducing their energy requirement for one of the most expensive organs in their bodies: the brain," van Schaik added.

"This brings us closer to a good ecological theory of variation in brain size, and thus of the conditions steering cognitive evolution," he said. "Such a theory is vital for understanding what happened during human evolution, where, relative to our ancestors, our lineage underwent a threefold expansion of brain size in a few million years."

In their study, Taylor and van Schaik focused on several varieties of orangutans, an endangered primate closely related to humans.

Members of the orang species inhabiting Sumatra, called Pongo abelii, live in the island's most favored environment, where soils are best for growing the fruits they most like to eat. "They'll eat fruits as often as they can, and they'll travel farther away for them if not nearby," Taylor said.

Sumatra also appears to be less subject to periodic "El Niño" climatic fluctuations that disrupt vegetative growth on other islands in the Indonesian region, the researchers' report said.

The scientists found that the nutritionally well-off Sumatran orangutans differed most strikingly from Pongo pygmaeus morio, one of the three subspecies occupying the island of Borneo. The morio subspecies lives in the northeastern part of the island where soils are poorer, access to fruit is most iffy and the impact of El Niño events can be significant.

Those factors "converge to produce an environment for orangutans of eastern Borneo that is at times seriously resource-limited," the scientists wrote. During extensive fruit-short periods, the animals have to "resort to fallback foods with reduced energy and protein content, such as vegetation and bark," they added.

In previous studies, reported in the April 2006 issue of the Journal of Human Evolution, Taylor found evidence that orangs living in Borneo's northeast have jaws that are better able to handle tougher varieties of food than orangutans in other parts of Borneo or Sumatra.

This improved feeding efficiency, coupled with a relatively small brain, would enable such animals to adapt to their conditions by both maximizing their resources and conserving energy, she said.

In addition, studies by van Schaik and other scientists have suggested that Borneo's morio orangs bear offspring more frequently than do Sumatra's orangs. Such relatively short intervals between births could themselves be tied to smaller brains in such higher primates as orangutans, van Schaik and Taylor wrote in their current report.

"Larger-brained apes have slower-paced life histories," they said. "Assuming selection is acting on brain size, life history is prolonged because development of larger brains require more time."

Their previous work led Taylor, an anatomist who studies bones, to begin collaborating with van Schaik, a field biologist who studies living orangs in the wilds, to address the question of whether nutrition, brain size and interbirth intervals might be linked.

Other scientists working in the 1980s had found no differences in brain size among orangs from Borneo and Sumatra, Taylor said. But that work sampled animals only from west Borneo and not from resource-limited east Borneo, she added.

In their own studies, as well as in studies by other researchers, "we see greater anatomical differences amongst the Bornean populations than we see between the Bornean and Sumatran populations," Taylor said.

In addition to having physical differences, Bornean orangs also inhabit areas that vary more ecologically than do comparative orangutan habitats on Sumatra. "The eastern parts of Borneo suffer more from El Niño-related droughts than parts of western Borneo," the scientists wrote. "The effects of El Niño on tropical rain forest composition and diversity are also more marked in eastern compared to western parts."

So Taylor and van Schaik undertook "a comprehensive re-evaluation of brain size among all orangutan species and subspecies," they wrote.

Since they couldn't measure brain size in wild, living members of these endangered animals, Taylor sought out skulls from museums and other sources. In all, they compared 226 adult specimens from the four distinct populations occupying Sumatra and Borneo.

Among these populations, orangutans of the Pongo pygmaeus morio species on Borneo "consistently exhibit the absolutely and relatively smallest cranial capacity," the researchers concluded. Although the researchers found reduced brain sizes in both male and female orangutans, the differences within the small group of animals studied were statistically significant only for the females, they noted.

As to what may cause the gender difference, the researchers note that female morio are notably smaller than their male counterparts and that they generally are at greater risk for nutritional stress because of pregnancy and lactation and their smaller homes ranges.

"The general scenario supported by these results, then, is that an increase in the frequency of uncontrollable periods of low energy intake in one part of the orangutan's geographic range selected for a reduction in brain size," the researchers said.

Similar evolutionary pressures within resource-poor environments also may explain the smaller-than-normal brain size of a controversial 18,000-year-old skull recently found on the Indonesian island of Flores, Taylor and van Schaik said in their article.

In announcing the find in 2004, the skull's discoverers suggested that the small-brained specimen represented a new dwarf early human species that somehow survived until fairly recently. Critics argue that it actually is a modern human afflicted with microcephaly, a genetic disorder characterized by an abnormally small head and an underdeveloped brain.

Web address: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/10/061023192505.htm